Storm of Steel - Some Notes on the English Translations and the German Historical-Critical Edition

A lot of false claims are made about the English translations of Storm of Steel. There are various reasons behind this, but the first thing to remember is that the original English edition is not the original in German.

The 1929 English edition is based on, I believe, the 1924 German edition which was itself heavily edited. More nationalist sentiments were added due to the conflicts at the time. The English edition released by Penguin is based on the last complete version released in German. Jünger himself edited the work throughout his life, the edits are not due to the English translator, a common misconception. One may then ask why Jünger edited his work, was it a political decision? A change in his philosophy? The pain of the 1930s and 40s? Difficult questions. The 1920 German edition is the original and closest to his journals. One may note the rough, or raw, quality which is the result of a distinction many World War I writers struggled with, the decision between the novel or journal style.

This is where Jünger's editing decisions can first be seen, they are stylistic rather than political interpretations and decisions for the reader, but most importantly for "those German men" he would always stand beside. It was not for the citizen to judge these men. In this sense, Jünger anticipated correctly how his most important work would be misread and misused by various groupings.

Then there are multiple versions with more or less significant edits. One, if I remember the date correctly, is in 1931. The final released edition is from 1962 (?), which is used for the Penguin edition. Then there are later edits and additions which have not been published, apart from a few shared by the estate for the German historical-critical edition.

A final note, much more is added in the later edition than is removed. This amounts to, I believe, at least a chapter across the whole book, or several 'journal entries' per chapter.

There were something like eight sections removed from the nationalist edition of 1924, and I would question only one of these edits ('The European of today was revealed for the first time here in battle.') The rest are too political and have little value in writing intended as a modern Iliad or Saga.

One will also find that a lot of the edits are simply single words, removed for literary reasons. For example, the assigned sector did not have to be repeated again and again. The historical-critical edition makes all of these edits clear, including what is removed and added in each edition. The later edition appears on the right-hand pages and everything is colour-coded for ease of use.

Which edition is recommended?

There are some advantages to the 1929 Creighton translation, it has a few additional passages from the nationalist years, the style is that of a common soldier so it can be gritty, but there are some mistakes and quite awkward sentences at times.

The Hofmann is more complete, and in the literary style of an academic. The additions, which Jünger himself introduced over the years, are generally of much higher quality than the nationalist passages and amount to a chapter of work. It is less a question of translation than of different German editions.

The Hofmann and Creighton translations are based on two separate editions, of which the later German edition includes a lot of improvements (which is never mentioned by those who promote the 1929 edition) and, as I said, about a chapter of additional material. There are 5-6 passages removed from the 1929 nationalist edition, I believe a paragraph or two in most cases. In my opinion only one of these passages has real literary merit, and amounts to one of the few editing choices by Jünger that I would question. The others result in a lesser work of art. Remember that Jünger was writing an Iliad or Saga for our time, the inclusion of political commentary is presents an extreme problem. Recall Hölderlin's nationalism which forms effortlessly within the work of art, Jünger rightly excluded the political form and allowed it to take shape in his other work.

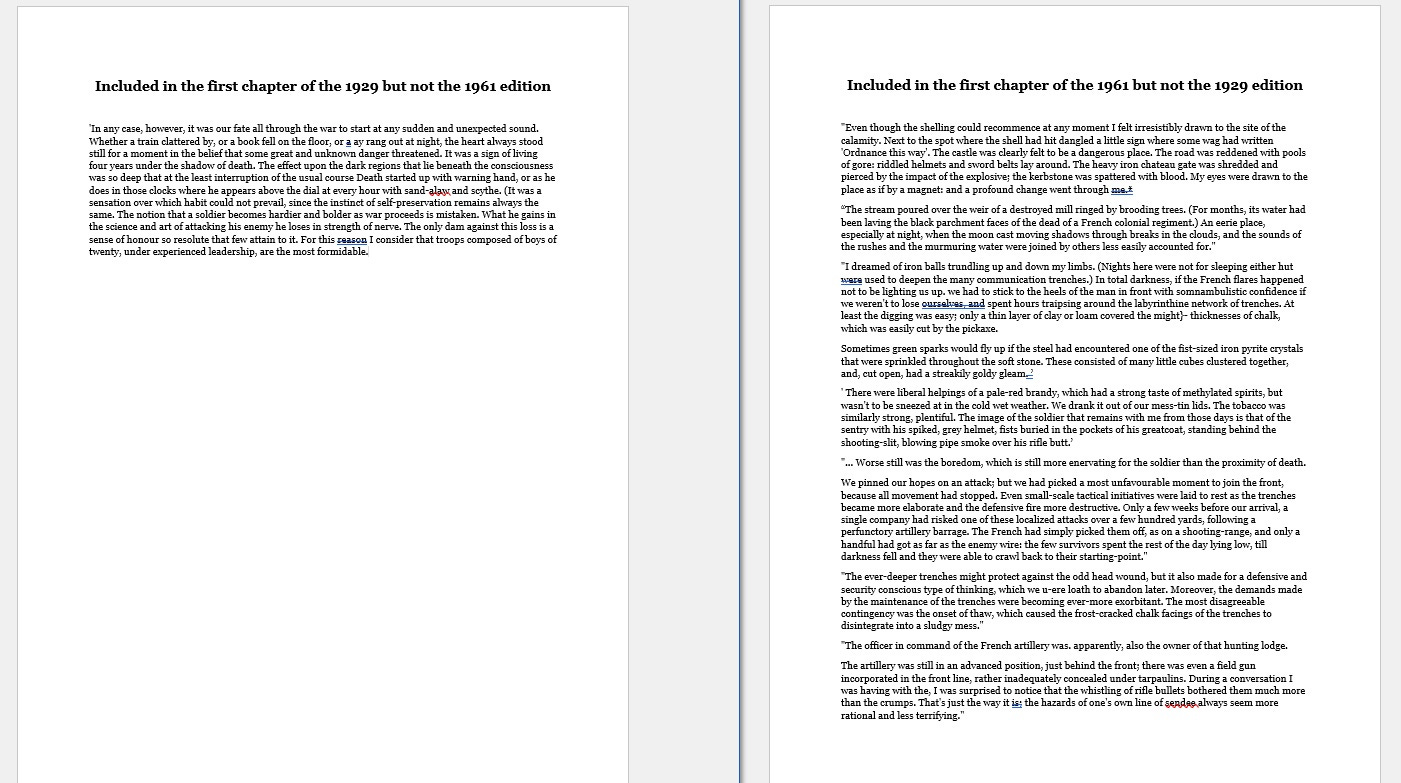

A comparison of the edits from the first chapter

Included in the first chapter of the 1929 but not the 1961 edition

'In any case, however, it was our fate all through the war to start at any sudden and unexpected sound. Whether a train clattered by, or a book fell on the floor, or a ay rang out at night, the heart always stood still for a moment in the belief that some great and unknown danger threatened. It was a sign of living four years under the shadow of death. The effect upon the dark regions that lie beneath the consciousness was so deep that at the least interruption of the usual course Death started up with warning hand, or as he does in those clocks where he appears above the dial at every hour with sand-glass and scythe. (It was a sensation over which habit could not prevail, since the instinct of self-preservation remains always the same. The notion that a soldier becomes hardier and bolder as war proceeds is mistaken. What he gains in the science and art of attacking his enemy he loses in strength of nerve. The only dam against this loss is a sense of honour so resolute that few attain to it. For this reason I consider that troops composed of boys of twenty, under experienced leadership, are the most formidable.

Included in the first chapter of the 1961 but not the 1929 edition

"Even though the shelling could recommence at any moment I felt irresistibly drawn to the site of the calamity. Next to the spot where the shell had hit dangled a little sign where some wag had written 'Ordnance this way'. The castle was clearly felt to be a dangerous place. The road was reddened with pools of gore: riddled helmets and sword belts lay around. The heavy iron chateau gate was shredded and pierced by the impact of the explosive; the kerbstone was spattered with blood. My eyes were drawn to the place as if by a magnet: and a profound change went through me.*

“The stream poured over the weir of a destroyed mill ringed by brooding trees. (For months, its water had been laving the black parchment faces of the dead of a French colonial regiment.) An eerie place, especially at night, when the moon cast moving shadows through breaks in the clouds, and the sounds of the rushes and the murmuring water were joined by others less easily accounted for."

"I dreamed of iron balls trundling up and down my limbs. (Nights here were not for sleeping either hut were used to deepen the many communication trenches.) In total darkness, if the French flares happened not to be lighting us up. we had to stick to the heels of the man in front with somnambulistic confidence if we weren't to lose ourselves, and spent hours traipsing around the labyrinthine network of trenches. At least the digging was easy; only a thin layer of clay or loam covered the might}- thicknesses of chalk, which was easily cut by the pickaxe.

Sometimes green sparks would fly up if the steel had encountered one of the fist-sized iron pyrite crystals that were sprinkled throughout the soft stone. These consisted of many little cubes clustered together, and, cut open, had a streakily goldy gleam. ’

' There were liberal helpings of a pale-red brandy, which had a strong taste of methylated spirits, but wasn't to be sneezed at in the cold wet weather. We drank it out of our mess-tin lids. The tobacco was similarly strong, plentiful. The image of the soldier that remains with me from those days is that of the sentry with his spiked, grey helmet, fists buried in the pockets of his greatcoat, standing behind the shooting-slit, blowing pipe smoke over his rifle butt.’

"... Worse still was the boredom, which is still more enervating for the soldier than the proximity of death.

We pinned our hopes on an attack; but we had picked a most unfavourable moment to join the front, because all movement had stopped. Even small-scale tactical initiatives were laid to rest as the trenches became more elaborate and the defensive fire more destructive. Only a few weeks before our arrival, a single company had risked one of these localized attacks over a few hundred yards, following a perfunctory artillery barrage. The French had simply picked them off, as on a shooting-range, and only a handful had got as far as the enemy wire: the few survivors spent the rest of the day lying low, till darkness fell and they were able to crawl back to their starting-point."

"The ever-deeper trenches might protect against the odd head wound, but it also made for a defensive and security conscious type of thinking, which we u-ere loath to abandon later. Moreover, the demands made by the maintenance of the trenches were becoming ever-more exorbitant. The most disagreeable contingency was the onset of thaw, which caused the frost-cracked chalk facings of the trenches to disintegrate into a sludgy mess."

"The officer in command of the French artillery was. apparently, also the owner of that hunting lodge.

The artillery was still in an advanced position, just behind the front; there was even a field gun incorporated in the front line, rather inadequately concealed under tarpaulins. During a conversation I was having with the, I was surprised to notice that the whistling of rifle bullets bothered them much more than the crumps. That's just the way it is; the hazards of one's own line of service always seem more rational and less terrifying."

Storm of Steel remains strangely absent from the recommended reading lists of the US Army and Marine Corps. The German edition of 1920 remains the standard for infantry combat that is being repeated today in Ukraine. It is what James Webb’s Fields of Fire was for Vietnam. What kind of men can endure the Storm of Steel? Those who are born to it and those prepared for it by reading Jűnger’s classic.