To the True Friedricha Nietzschego

First of a Meta-perspective on the Titan

“I feel strengthened in my instinctive aversion to the Eternal Return. Nietzsche wanted to bite the head off the snake; one of his anxiety dreams.” - Ernst Jünger

Some see him as a titan of the age, one who “thinks what now is.” Nietzsche, the pantheon and altar of the democratic war, he who is to birth its son. It would seem impossible that an heir would turn against him, and especially his one true heir. Yet, Ernst Jünger showed signs of turning against him, a conflict of masters. There are images and short passages which reveal an earth conflict, between two titans, of instincts and metaphysical law.

Jünger turns to a Christian reflection, “Passing and becoming are not eternal.” Nietzsche wanted to bite the head off of the snake, in this is his fear of pain. The eternal return is a return of the eternal fall. Becoming as meta-instinct, total decision and reflection in each moment, the absolute weight of a dead world. This is also the fear Hobbes was born with, but Nietzsche can have no twin.

A naïve question, if there is no truth can there be a true Nietzsche? Or does he become for us only a perspective? Jünger, despite being the only true heir to Nietzsche, was cursed with observation, with a search for truth, what is actual – the possible, the will, is something that we must give shape to. There must be a morality of the will. In the end he sided with Nietzsche's greatest opponents, including the Christians.

Nietzsche wanted the possible to be imprinted upon the actual, and to such an extent that the actual becomes impossible. This is the source of the will to power, a destructive will which must be made eternal. The eternal return is, rather than a morality of the will, a boundlessness of the will. And it is also an end, the death of the will. This is because there can be no boundlessness without limits, just as there can be no becoming without being. Such contradictions can only build up, like a ridiculous mountain, and what is found is only what was already there in the beginning – nothing.

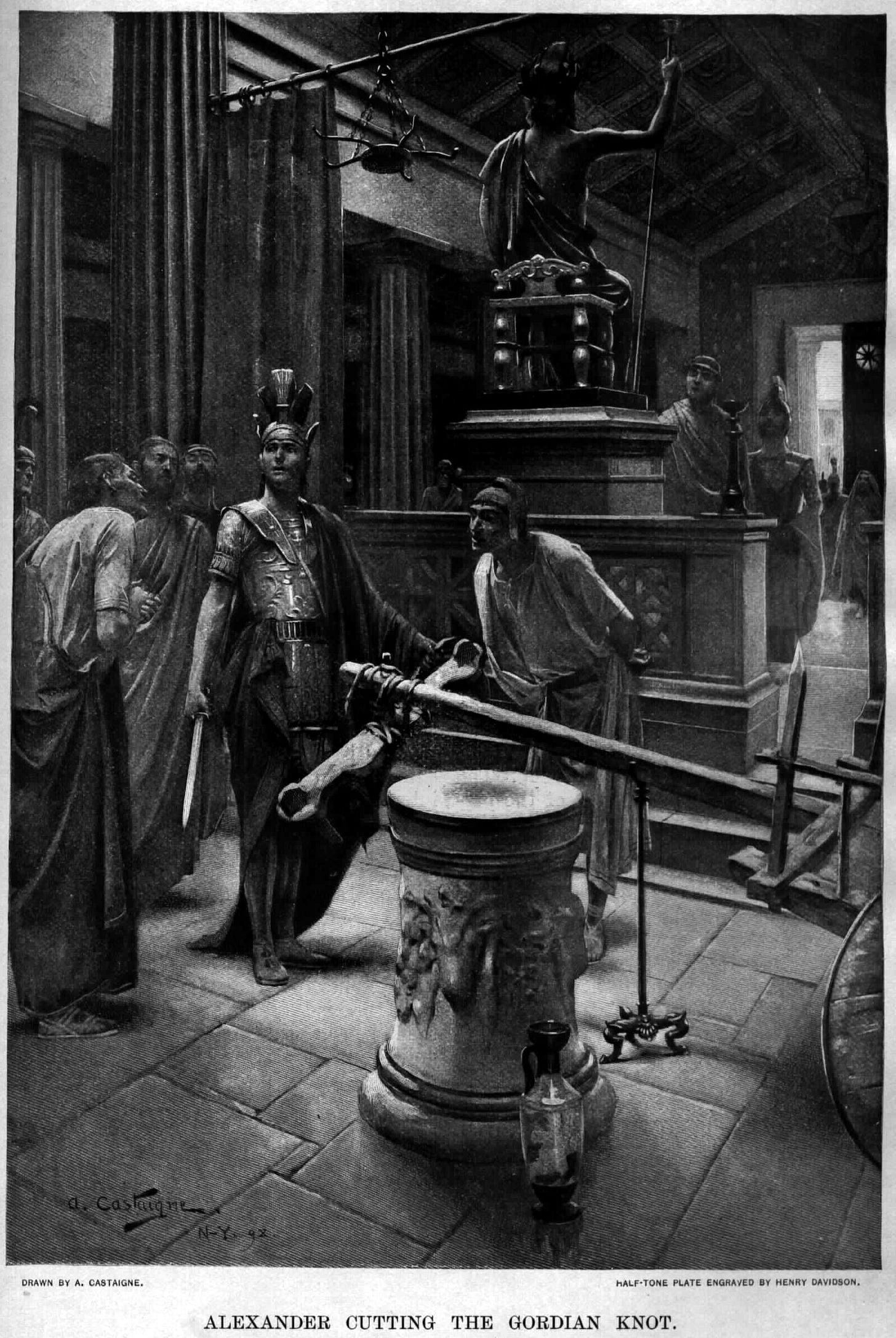

Nietzsche, in his wandering, became lost in the Greek world, a dead world. This was his hatred for life, experienced as instinct, fate – not as reason and law, which he hated in so many of the Greeks. What he could not see was that reasoning and law were bound together in the Greek world, impossibly like the Titans and Olympians, like the Gordian Knot. The lesson of Alexander: one can unbind the knot as instinct, but it must be bound again as law.

We might follow Hölderlin – there is a Gordian Knot between ages, and also within the individual, who is absolute. One cannot cut “the eternal knot, the contradiction between art and genius, between freedom and organic necessity.” One must freely choose –– in the very phrase we see that the determined is bound to freedom, one cannot escape the eternal law. "Everything depends on the fact that the I does not just remain in a reciprocal relation with its subjective nature, from which it cannot abstract without cancelling itself out."

Nietzsche insists this is possible, that it is imperative to the I. "I am I" and nothing else. The individual cuts the eternal knot and becomes eternal. But this is impossible, because there can be no eternity without limitation, there can be no being without passing. Becoming, as eternity, amounts to imprinting itself upon nothing.

This is perhaps what Jünger sensed in the eternal return, and why he sided with Hölderlin and the Christians. What else might fall from the hand of the great titan?